Our Zope 3 application had a speed problem: a view used to export an XML

file with user data stored in the ZODB took two thirds of an hour. Clearly,

the time to optimize it has arrived.

I've been indoctrinated by reading various sources (Federico Mena-Quintero's

blog is a good one) that you must do two things before you start fiddling

with the code:

- Create a reproducible benchmark

- Profile

Step one: benchmark. A coworker convinced me to reuse the unit/functional

test infrastructure. I've decided that benchmarks will be functional doctests

named benchmark-*.txt. In order to not clutter (and slow down) the

usual test run, I've changed the test collector to demote benchmarks to a lower

level, so they're only run if you pass the --all (or --level 10) option to the

test runner. Filtering out the regular tests to get only the benchmarks is

also easy: test.py -f --all . benchmark.

Next, the measurement itself. Part of the doctest is used to prepare

for the benchmark (e.g. create a 1000 random users in the system, with a fixed

random seed to keep it repeatable). The benchmark itself is enclosed in

function calls like this:

>>> benchmark.start('export view (1000 users)')

...

>>> benchmark.stop()

The result is appended to a text file (benchmarks.txt in the current

directory) as a single line:

export view (1000 users), 45.95

where 45.95 is the number of CPU seconds (measured with time.clock)

between start/stop calls.

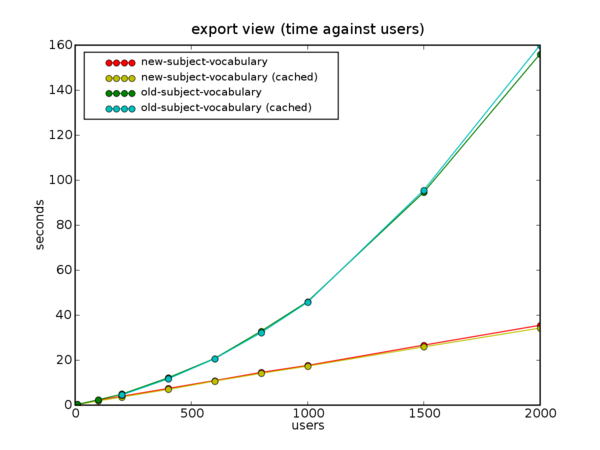

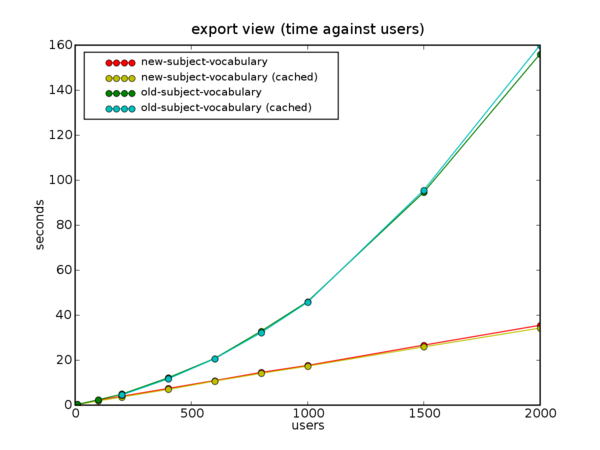

Next, I experimented with various numbers of users (from 10 to 2000) and

recorded the running times:

export view (10 users), 0.25

export view (10 users), 0.26

export view (100 users), 2.33

export view (200 users), 4.81

export view (200 users, cached), 4.47

export view (200 users), 4.91

...

export view (2000 users), 155.96

export view (2000 users, cached), 159.91

The "cached" entries are from the same doctest run, with the benchmark

repeated a second time, to see whether ZODB caches have any effect (didn't

expect any, as functional tests use an in-memory storage, and besides all

the objects were created in the same thread).

Clearly, the run time grows nonlinearly. Some fiddling with Gnumeric

(somewhat obstructed by Ubuntu bug

45341) showed a pretty clear N**2 curve. However it is not fun to copy and

paste the numbers manually into a speeadsheet. A couple of hours playing with

matplotlib and cursing broken

package dependencies, and I have a 109 line Python script that plots the

results and shows the same curve.

Step two: profiling. (Well, actually, I did the profiling bit first, but at

least I refrained from changing the code until I got the benchmark. And it would

have been easier to profile if I had the benchmark in place and didn't need to

do it manually. For the purposes of this narrative pretend that I did the

right thing and created a benchmark first.)

A long time ago I was frustrated by the non-Pythonicity of the profile module

(my definition of a Pythonic API is API that I can use repeatedly without

having to go reread the documentation every single time) and wrote a @profile function decorator.

This came in handy:

class ExportView(BrowserView):

template = ViewPageTemplateFile('templates/export.pt')

@profile

def __call__(self):

return self.template()

One run and I see that 80% of the time is spent in a single function,

SubjectVocabulary (users are called subjects internally, for historical

reasons). It is registered as a vocabulary factory and iterates through all

the users of the system, creating a SimpleTerm for each and stuffing all of

those into a SimpleVocabulary. It was very simple and worked quite well until

now. Well, now it's being called once per user (to convert the value of a

Choice schema field into a user name), which results in O(N2)

behavior of the export view.

A few minutes of coding, a set of new benchmarks, and here's the result: